NYC sunrise, December 21, 2016

True tests

Creating a successful company is a low probability endeavor. A series of small, low-likelihood-of-success activities over the course of several years compound to create a great result for those lucky (or foolish) enough to be part of the journey.

If I think back to the early days of onefinestay, it often felt like landing a particular hire, or a valuable customer — having a conversation go one way, or the other — could make the difference between success and failure. It felt like failure was always looming in the background. And what’s scary is that this feeling was probably accurate enough.

Most startups don’t succeed. But how does this play out on the ground? Its a customer or an investor saying no, inability to adapt to changing market conditions, the loss of a critical team member.

So with the obstacles that every new business faces, how to do you maximize probability of success? This comes down to ensuring all critical business activities are true tests.

The idea of a true test is simple — every time the business encounters a life-or-death strategic opportunity, it needs to pull out all of the stops to stack the outcomes in its favor. If you line everything up, do everything in your power, and fail, at least you know it was a true test. It wasn’t meant to be, and you can move on to the next challenge with heads held high.

If you don’t — how can you be sure success wasn’t a possibility?

Here are the questions I ask myself in order to determine whether we’re giving an initiative a true test:

- Are our best (& best suited) people on it?

- Have we allocated, and ring-fenced, the appropriate amount of financial resources for a successful outcome?

- Have we lined up the organizational support required to succeed? If its a hire, or investment— are our expectations of terms reasonable?

- Are our timelines sound, and can we continue to support this initiative if things don’t go exactly to plan (in my experience, new business initiatives take 6–12 months to ripen)

In the early days, many opportunities can have a huge impact on company success. As companies scale, the percentage of life-or-death situations tends to decrease, and this is how leadership teams create leverage and scale. However, its also at this time that leaders can lose sight of must-win activities, or under-resource strategic opportunities in favor of business-as-usual. This is often when the company starts losing.

Here are some examples of activities that require true tests, regardless of company stage:

- Hiring a critical member of the leadership team

- Launching a major new product, or expanding to a new market

- Raising external capital

- Investing in a new sales or marketing channel with strategic potential

- Landing a huge new customer account

Organizations need to always put their best feet forward for the must-win activities. Only then is it possible to know whether the result was the best of all potential outcomes.

Pouring out the jellybeans

Q4 is the time of year when most companies plan their strategy for the next year. Depending on the stage and nature of the company, this can be an informal process between co-founders on a spreadsheet, or a formal multi-month process with various stakeholders and approvals.

Jim Collins in Good to Great talks about ‘Stop Doing Lists’. The annual planning process is a great time to formulate a list like this headed into the new year. It’s easy to not only have too many initiatives for the following year (Fred Wilson blogged today that the ideal number is 3–5), but to also carry forward initiatives that no longer deserve the resources or support of the business.

Stopping activities that are already embedded in the organization is often much more difficult and emotional that cutting down a new initiative list.

Last week I attended a talk by Dwell CEO Michela O’Connor Abrams who described her company’s planning process. At the end of every year, her leadership team sets priorities by ‘pouring all of the jellybeans out on a table’, and then decides — one by one — which jellybeans to put back in the jar for the following year.

I thought this was a nice way of describing how to build a continuous improvement culture where all ideas can be shared and there are no sacred cows. Too often business activities that add no strategic value, or used to work and now don’t, survive for years, sleepwalking their way through the organization year after year.

Jim Collins coined talks about ‘conducting autopsies without blame’ when things go wrong — however often waiting until things go wrong doesn’t account for the opportunity cost of doing things that aren’t fully broken, but also not leading to a strategic outcome.

This practice should apply to all companies of all sizes and industries. I’ve seen plenty of startups that thought they were the disruptor turn into the disrupted because they were holding on too long to things that weren’t working.

Time and money are both highly scarce commodities in companies. Its important to constantly reassess whether these resources are directed towards the highest value activities.

Strategy & tactics | what & how

Tactics and strategy are easy to confuse. Andy Grove summarizes the difference well:

As you formulate in words what you plan to do, the most abstract and general summary of those actions meaningful to you is your strategy. What you’ll do to implement the strategy is your tactics. (High Output Management)

In other words, the strategy is the what, and the tactics are the how.

Top-level alignment on strategy is critical at a company — the few people in charge need to ensure that they agree on direction of travel. This can often be accomplished through a regularly scheduled leadership meeting. If the leadership team is distributed globally, meeting in-person at an offsite every 6–12 months is also an efficient way to hammer out strategy.

However, the ‘what’ is often easy to align on, and boils down to specific initiatives to either grow (increase basket sizes, expand to new markets, make more product) or reduce costs (lower CAC, reducing fulfillment costs, insource vs outsource decisions). Measurement of the what is critical, and frameworks such as OKRs can help do this.

However, the ‘how’ can be much harder to align on. In a startup environment without a well-oiled business model, there are always various ways of pursuing the same strategy. But not all methods have the same likelihood of success or the same cost & resourcing requirements, and as initiatives unfold information asymmetry means tradeoffs on the how are constantly being made. It may turn out that the strategy that was agreed initially looks very different as it makes its way through implementation — or was misunderstood even to begin with.

So, make sure you regularly put in the extra effort — after the offsite or the weekly management meeting — to ensure there’s alignment not just on what to do, but how to do it.

5 Minute Book Review: Sapiens

This past week I read Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. It's a fresh take on the story of human evolution, and how we ended up rising to the top of the evolutionary chain.

The punchline is that our ability as humans to tell abstract stories enabled us to cooperate on a much larger scale than our ancestors. Instead of being confined to an extended social group (like chimpanzees or Neanderthals), we invented concepts like religions, nation-states, and (eventually) corporations. Because we have the cognitive ability to believe in these abstractions, we blew through social limits of group size (~150 individual members, similar to Dunbar's number popularized in the Tipping Point) and took over the world.

However, what success looks like from an evolutionary perspective isn't the same thing as success for the individuals within the evolutionary system. Was a major turning point in our history - the Agricultural Revolution - really a good thing for the individual? As the hunter-gatherer lifestyle evolved to farming, on average our diets became less varied, work hours became longer, and we became less healthy. Our exposure to illness, the strain on our bodies from work we weren't evolutionarily designed for, famine - all increased in the early days of agriculture. As articulated in the book:

Humanity’s search for an easier life released immense forces of change that transformed the world in ways nobody envisioned or wanted....A series of trivial decisions aimed mostly at filling a few stomachs and gaining a little security had the cumulative effect of forcing ancient foragers to spend their days carrying water buckets under a scorching sun.

The Agricultural Revolution was neither good nor bad - it just happened. It was good for the proliferation of our DNA (once we became more sedentary - and our babies could subsist on grain rather than breast milk, our family sizes increased and the human population exploded), but for thousands of years made our lives more mundane. And there was no going back - very quickly we forgot the skills required to be effective hunter-gatherers.

(side note: this reminded me of how startups as they raise capital & scale often lose the organizational memory of what it meant to be a startup in the first place, which can quickly create problems for the business)

The Scientific Revolution, which began as Europeans set foot on America about 500 years ago, has seen the quality of life for humans recover - but the same can't be said for the other species we took along with us from the Agricultural period - domesticated chickens, pigs, cows. There are now more than a billion cows and 25 billion chickens in the world as part of our industrial food chain living a heartbreaking life of solitude, poor health and separation from family.

The discovery of America catalyzed a fundamental shift in Western psychology. If there is a new world out there - with its own native cultures, flora, fauna, climate - what else don't we know? This led to the modern Scientific age - where the assumption is we don't know, and there's always more to discover through research and exploration. This idea became deeply ingrained into the European psyche. The religious order and the bible had been the source of truth up until this point. This nonstop push for more knowledge forms the basis of the modern era.

We now live in the most peaceful time in our history, have largely eliminated the various issues (at least for humans) brought about in the Agricultural Revolution, and live in a time of unprecedented pace of scientific & technological discovery. It's very easy to argue that its the best time to be alive in human history.

What is still easy to miss is how our evolutionary success and higher quality of life should in turn lead to a happier life.

Writing more, less perfectly

There’s a quote often attributed to Sheryl Sandberg: “done is better than perfect”.

My blogging has been based off of ‘perfect’ for the past few years - if the idea wasn’t quite right, I didn’t write. I had an idea in my head of what a blog post should look like - length, originality, grammar, etc., and this was the baseline standard to post.

The implication of this for me was that I’ve been writing and posting less than I’d like to.

This past week I’ve been reading the new Tim Ferris book, Tools of Titans. In the book, James Altucher talks how perfection kills idea generation - so, ‘if you can’t generate 10 ideas, generate 20’ (accepting - without fear - that the majority of these ideas will be bad). Through this process, more good ideas surface on an absolute basis than trying to think about a handful of perfect ideas. Openness to bad ideas leads to discovering important ideas.

As I attempt to write more, I’m hopeful the effect will be the same for me.

5 Minute Book Review: High Output Management

I’ve wanted to read Andy Grove’s High Output Management for a few years after it was endorsed by Ben Horowitz in his blogs and book. I finally got around to it last month.

High Output Management was written in the mid 80s, and shows its age. It reads like an engineer’s approach to management 101, which came across a technical and emotionless at times, but its a good counterbalance to the softer management books I’ve become accustomed to - Setting the Table, Peak, Pour Your Heart Into It. At the same time, a results-driven, output based approach to management cuts through the noise- I found it to be refreshing. And there are some great rules of thumb that can be applied to daily management practice.

It starts with a basic realization - management is not about the manager, at all. Its solely about serving the organization beneath and adjacent to you for the best outcomes.

Here were my favorite few tidbits:

A manager’s output = the output of his organization + the output of neighboring organizations under his influence - its a simple equation, but I found the addition of the second part to be profound. All too often its easy to confuse ‘management’ with ‘resources under me in an organization’, and as such undervalue the role of specialist & individual contributors without large functions. Yet often these contributors are the glue that holds an organization together and essential to successful outcomes.

On one-on-ones - the frequency of communication with subordinates depends on how well suited they are to the job they’re being asked to do - their ‘task level maturity’. I don’t personally subscribe to this - I catch up with all of my direct reports every week. However recognizing that different levels of experience may require a different communication frequency is valuable.

Separately, one-on-ones are about making the direct report most effective, not for the manager to discuss all of his problems.

On time management - the main scarcity any manager has is time. This means managers should focus solely on high leverage activities - activities that efficiently cascade through the organization. I would add that managers should focus activities that only they specifically are able to do - and delegate everything else. And treat time as a sacred commodity - as Andy says,

Just as you would not permit a fellow employee to steal a piece of office equipment worth $ 2,000, you shouldn’t let anyone walk away with the time of his fellow managers.

How many direct reports? - optimal number is 6-8

How big can decision-making meetings get? No more than 8 people, ideally 6 or 7.

Take meeting minutes - its a small incremental investment in what has been a very large investment - gathering a group of people for an hour or so to discuss the business.

On the purpose of performance reviews - its not so the manager can get all of the feedback over the year off of his chest and feel better. It is solely to improve the performance of the person. Focus on a few key themes with a few associated actions.

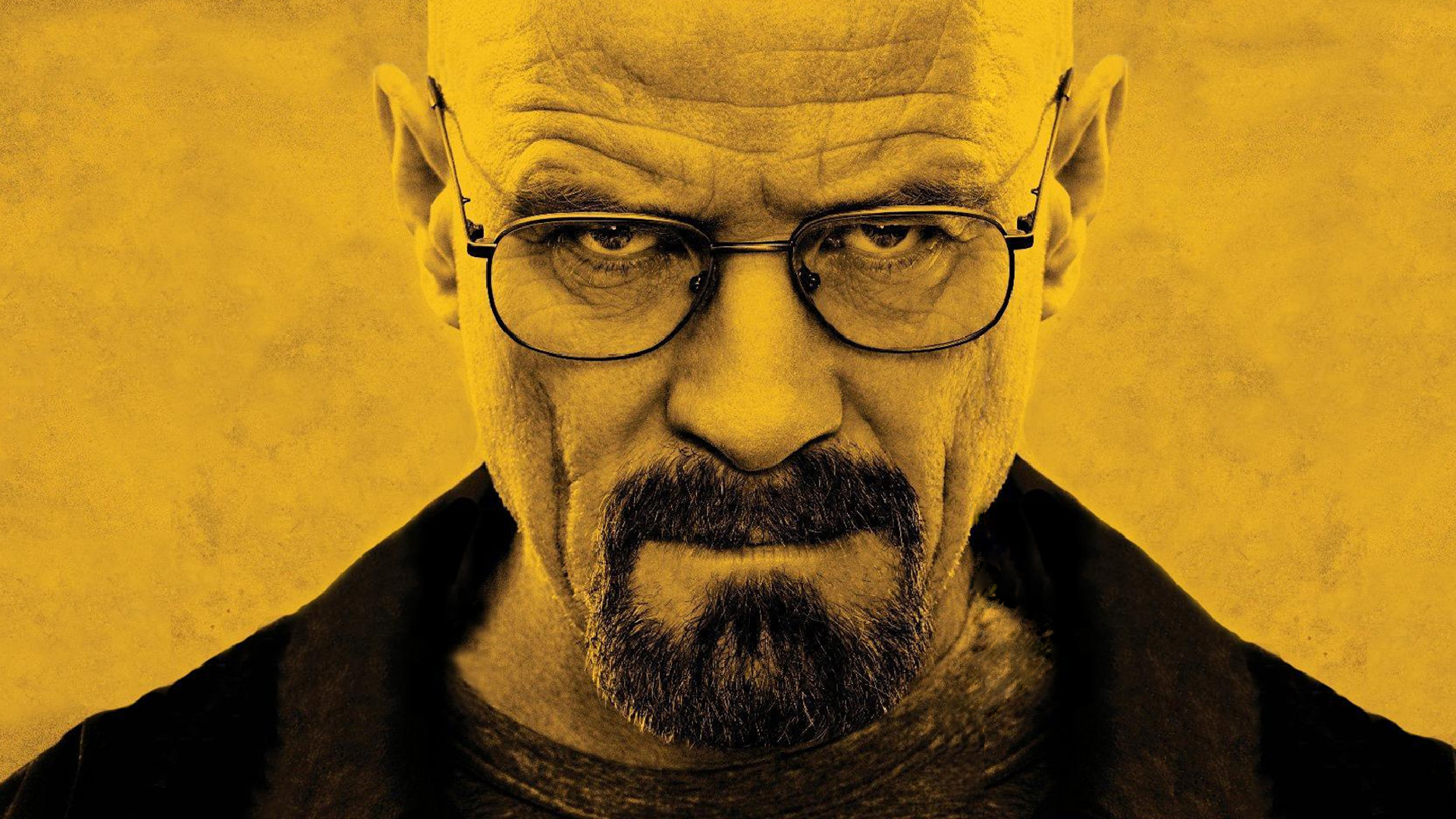

Lessons from Bryan Cranston’s ‘A Life In Parts’

I finished Bryan Cranston’s new memoir, A Life In Parts, over the weekend. Most people now know Cranston’s work due to his epic portrayal of Walter White in Breaking Bad — one of the most complex & rich characters crafted in the past decade — but he has been acting and hustling for nearly 40 years.

Achieving greatness in one’s specific vocation or enterprise has a lot of commonality with greatness generally in any pursuit.

Here are some of my key takeaways:

- Peak performance relies on presence — technical skills and preparation are necessary, but can only get you so far. What makes a performance great is an openness to the range of emotions any character could be feeling in the moment. What are the possible emotional levels my character could experience? I break the scene down into moments or beats. By doing that work ahead of time, I leave a number of possibilities available to me. I stay open to the moment, susceptible to whatever comes.

- Bring it all — Cranston’s portrayal of LBJ on Broadway was the culmination of a lifetime of his experiences, both professional and personal. We are all the product of our experiences. His relationship with his parents, gigs that didn’t work out so well, how he was feeling on the day. Authenticity cannot be crafted — its the sum of what’s happened in life up until this point. You’re hungry. Use that. You caught a cold. You have a sinus infection. LBJ is dealing with these same maladies on stage, blowing his nose, hacking away. You bring everything you are on stage with you. And you see if it can fit into the character.

- Trust and mutual respect is the bedrock of culture — Breaking Bad’s success was the result of the interplay between the actors, writers, producers & crew. The show worked because of shared respect for the perspectives of the various players. If trust breaks down, its hard for the culture to be preserved — this puts everything at risk. This is why a member of the crew was let go immediately after disrespecting team members at Breaking Bad Bowling Night (despite this individual having his own demons to contend with). But there was no way we could let him be part of what we were trying to do. We couldn’t let anyone put at risk this thing we’d worked so hard to create.

- Everything counts — in the late 90s, Cranston auditioned for a character, Patrick Crump, in an episode of the X-Files. This is how he met Vince Gilligan. Subsequently, Cranston spent 7 seasons happily playing the goofy dad on Malcolm in the Middle. But his performance in X-Files left an impression on Gilligan, who sent him the script for Breaking Bad 8 years later. At the time, Cranston was ready to do an 8th season of Malcolm. Every negative has a corresponding positive. So many twists of fate and accidents of timing that seemed, in the moment, insignificant or unfortunate or even like rotten luck, and they all led me to this part.

- Explore things that scare you — it often means there’s something personally meaningful hiding behind it. If I’m considering a role and it makes me nervous, but I can’t stop thinking about it — that’s often a good indication I’m onto something important.

Cranston’s story is also perfect example of the myth of overnight success. His ‘moonshot’ happened in his 50s — on the foundation of a career of singles and doubles (and plenty of failures, too). This is a great lesson for anyone who thinks its too late to pursue their professional or personal dreams. I certainly relate to this, thinking about the baggage I carried around when I left the comfy world of venture capital to start my first company (in my 30s, with a kid on the way). Instead of feeling weighed down our prior experiences, we can reframe our past as bringing us all to this very moment in our lives — and try to make something great happen.

Mindful transitions for a better day at work

One of the most challenging aspects of leadership amongst the chaos and diversity of an average day is staying in the present moment and giving full attention to whatever activity is happening at that time.

Here’s some common occurrences in my life that I am working on improving:

Morning fog — Wake up. Check email 5 minutes after waking. Respond to emails I can respond to with one line, star others. Spend rest of morning at home drafting and (re)drafting responses to emails in my head I didn’t have time to respond to — when I want to be a fully engaged father and husband.

Meeting logjam — a first meeting juts up against the second meeting, and ends with a speedy ‘OK great — I have another call starting, lets talk soon’. Second meeting begins, and I’m still thinking about actions and unresolved items from the first meeting. For the first 5 minutes of the second meeting, I’m somewhere else.

1-on-1 stupor — a recurring 1-on-1 meeting begins and I haven’t consciously thought about the agenda. I spend the first few minutes talking out loud to figure out what should be discussed in the meeting.

Email wedge — I haven’t checked email in an hour or two, so I spend 3 minutes before a meeting filling myself in. See morning fog, above.

Evening fog — after the kids go to sleep, to unwind I watch a Netflix show and every few minutes check email with my iPhone next to me. I miss various lines from the show but respond within minutes to emails that come in out-of-hours.

Bringing your day to bed — I have trouble falling asleep thinking about an issue from the day, or a live email discussion that wasn’t fully resolved before lights out.

All of the above in one way or another relate to how I transition from one activity of my day to another. Here are some practices that I’ve introduced to transition with intention, & stay focused and energized:

- Create 5–10 minute buffers throughout the day — an extra few minutes minutes is surprisingly sufficient to 1) ensure that prior meetings are closed out appropriately and formally — actions are clear, next steps documented and 2) enter the next meeting consciously with a clear head, having spent a few minutes mentally revisiting purpose of the meeting. Google calendar’s speedy meeting feature is a great facilitator for this.

- Use physical notebooks — besides creating a better rapport as humans, not having a screen open during meetings avoids the temptation to check IMs or emails. This keeps the conversation flowing. Later I transcribe the key points to Evernote at a later time- or just photograph the page.

- Make email checking a proactive, conscious act — rather than pulling out a phone and checking email mindlessly throughout the day, I’ve tried to set aside time specifically for checking and responding to email. We live in a fast-paced world, but not so fast that a several-hour turnaround time is inappropriate. For more urgent matters, there’s always the phone.

- When in doubt — don’t check. I find that the stress of not knowing can easily be forgotten — but the churning of a response in my head stays with me.

- Use commute home to transition to ‘home mode’ — its tempting to continue to check or engage in work after I’ve left the office. In my case, I know I will be logging back in later in the evening, so I use my commute home to put the phone down and set my intention of being a dad and husband again.

- Save contentious communication for the work day — not every email or phone conversation can be pleasant- however, I don’t engage in debate or unharmonious communication outside of work hours if I can at all avoid it.

- Set boundaries—I try and have a hard cut-off time for email in the evening to allow myself to transition to ‘sleep mode’. This is typically 30–60 minutes before I go to bed. And I’ve long since moved my iPhone out of the bedroom to avoid that temptation.

Tying everything together is a meditation practice that I aspire to be a daily occurrence — however, I’ve found that even a small amount of conscious breathing throughout the day keeps me on point.

Manhattan sunset - May 14th, 2016